- Number 395 |

- August 19, 2013

NREL adds eyes, brains to occupancy detection

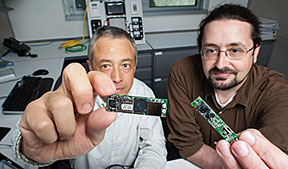

IPOS developers Luigi Gentile Polese and

Larry Brackney sit at a building automation control

network while showing the small size of the

essential parts of the IPOS – the microprocessor

and the camera. Credit: Dennis Schroeder

It's a gnawing frustration of modern office life. You're sitting quietly — too quietly — in an office or carrel, and suddenly the lights go off.

Installed to save energy, the room's occupancy detector has determined that no one is around, so it signals the lights to turn off. You try flapping your arms to get an instant reset, and if that doesn't work, you get up, walk to the light switch, and turn the lights back on manually.

The next morning, you put duct tape over the sensor to keep it from working, or you ask maintenance to turn down its sensitivity — so it won't turn off the lights until it detects no motion for a half-hour or hour. And of course, that quashes the primary purpose of motion detectors, which is to save the company a lot of dollars on its electricity bill.

For 30 years, occupancy sensors have relied primarily on motion detection. But now there's something new.

DOE's National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has developed and made available for license the Image Processing Occupancy Sensor (IPOS), which combines an inexpensive camera and computer vision algorithms that can recognize the presence of human occupants.

Today, lighting represents the largest electric load in U.S. commercial buildings—38% of total electricity, equating to $38 billion spent annually (on 349 billion kilowatt hours at $0.11 per kilowatt hour). Low-cost IPOS detectors ($100 to $200 per unit) that replace traditional motion-sensing technology can improve occupancy-detection accuracy by more than 20%, leading to enormous energy savings. Ninety-three percent of commercial space in the United States has no motion detection system at all, even though such systems now are mandated for new construction.

IPOS can detect with almost 100% accuracy the number of people in an area, spots where there are no people, the level of illuminance, and other variables.

"People have been playing with using image processing for occupancy detection for quite a while," said NREL Senior Engineer Larry Brackney, who developed IPOS with NREL colleague Luigi Gentile Polese. "What's novel about IPOS is that it's not just an occupancy sensor. It combines a lot of capabilities — occupancy detection and classification; how many people are in the space; are they sitting still or moving around? Where are they in the room? It offers the potential of putting light or ventilation only where it's needed. All functions are combined in a single sensor, and it's done in a way that is more robust than current sensor technology."

Its combined powers can, for example, detect that there are five people walking down Aisle 5 at a retail store, but none in Aisles 4 or 6. It can signal the lights to stay on in Aisle 5, but dim somewhat in the other two aisles. Big-box retail stores, reluctant to even dim the lights if customers are anywhere in the store, currently miss out on big energy savings because their existing motion sensors aren't accurate enough to detect vacancies by aisle or section.

What's more, an IPOS system set up in a big-box store could not only help save energy, but could also be used to play videos or commercials when occupants approach a screen or an exhibit, or to control animations for promoting products or services.

And in an office environment, IPOS can detect if there are people staying late, no matter how still they're sitting, and deliver that information so the building uses just the lights that are needed — no more, no less. The information can also be used to make instantaneous decisions on the amount of ventilation, air conditioning, or daylighting the occupants of the office need at that particular moment. And it can signal when security officers should be alerted.

In all, IPOS raises the accuracy of occupancy detection from about 75% to the upper 90% range.

Brackney and Gentile Polese said they started working on the idea for IPOS because office managers were expressing frustration with sensors that had too many false positives and false negatives.

But the timing was important too. IPOS can be made economically because it borrows from the technology of smartphones — commodity devices that combine a camera and a microprocessor and now sell for a modest price because so many of them are produced.

IPOS's field of view is a 45-degree angle, much like most cameras, Gentile Polese said. "But its range is much longer than traditional occupancy detectors." Instead of a 20-foot-long detection field, a single IPOS device can detect faces and human activity up to 100 feet away.

The sensors will likely sell for between $100 and $200 once a licensee starts producing them in volume.

IPOS is comprised of a small camera sensor integrated with a high-speed embedded microprocessor and novel software modules. The device is small; in fact, the embedded computer is the size of a stick of gum.

In office buildings, the camera-based technology could draw objections from employees. However, IPOS has the ability to keep the images out of the wrong hands, Brackney said. "The microprocessor on the sensor captures the image, analyzes it, and then destroys it" soon after processing, and it never leaves the device.

"We also have the capacity to blur the images" if there is worry about privacy invasion, Gentile Polese said. "It's trained to detect faces of people and human traits, but not to detect what kind of faces and what kind of people."

A recent assessment of IPOS's potential by the Bonneville Power Administration found projected savings of up to $144 million with an investment of $250,000 in IPOS technology. That's a return of $576 for every $1 invested.

IPOS is currently being tested in a few environments, including a large retailer in Centennial, Colorado, that serves as a test bed for innovations that could later be launched nationwide.

At the store, IPOS devices are trained on the large walk-in freezers and refrigerators in the back. They are helping determine the energy loss when, say, doors are left open after stocking the shelves with food.

"One of the really exciting things is that this combines sensing technology with the retail market's need for a security system that can save energy as well," Brackney said.[Bill Scanlon, 303.275.4051,

william.scanlon@nrel.gov]