- Number 429 |

- December 22, 2014

Protons hog the momentum in neutron-rich nuclei

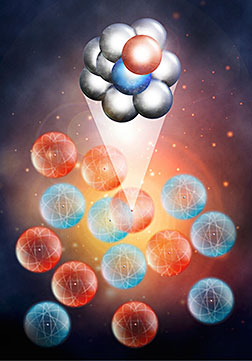

Illustration of Jefferson Lab's CEBAF Large

Acceptance Spectrometer, along with an

event reconstructed from the data. In this

experiment, an incident 5 GeV electron

scatters from a nucleon that has briefly

paired up with another in a short-range

correlation. Jefferson Lab's CEBAF Large

Acceptance Spectrometer completely

surrounds an experimental target and is

roughly spherical, measuring 30 feet

across. As particles flying out of the

target enter the detector, their paths are

bent by a magnet and are measured by

successive layers of different types of

particle detectors.

Like dancers swirling on the dance floor with bystanders looking on, protons and neutrons that have briefly paired up in the nucleus have higher-average momentum, leaving less for non-paired nucleons. Using data from nuclear physics experiments carried out at the Department of Energy's Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility, researchers have now shown for the first time that this phenomenon exists in nuclei heavier than carbon, including aluminum, iron and lead.

The phenomenon also surprisingly allows a greater fraction of the protons than neutrons to have high momentum in these relatively neutron-rich nuclei, which is contrary to long-accepted theories of the nucleus and has implications for ultra-cold atomic gas systems and neutron stars. The results were published online by the journal Science.

The research builds on earlier work featured in Science that found that protons and neutrons in light nuclei pair up briefly in the nucleus, a phenomenon called a short-range correlation. Nucleons prefer pairing up with nucleons of a different type (proton preferred neutrons to other protons) by 20 to 1, and nucleons involved in a short-range correlation carry higher momentum than unpaired ones.

Using data from an experiment conducted in 2004, the researchers were able to identify high-momentum nucleons involved in short-range correlations in heavier nuclei. In the experiment, the Jefferson Lab Continuous Electron Beam Accelerator Facility produced a 5.01 GeV beam of electrons to probe the nuclei of carbon, aluminum, iron and lead. The outgoing electrons and high-momentum protons were measured.

"We found this dominance of proton-neutron pairs in the nuclei we studied. What's striking is this pair-dominance all the way to lead," says Doug Higinbotham, a staff scientist at Jefferson Lab and a lead coauthor on the paper.

Then the researchers compared the momenta of protons versus neutrons in these nuclei. According to the Pauli exclusion principle, certain like particles can't have the same momentum state. So, if you have a bunch of neutrons together, some will have low momentum, and others will have high momentum; the more neutrons you have, the more high-momentum neutrons you would see, as they fill up higher and higher momentum states.

But according to Higinbotham, that expected picture is not what the researchers found when they measured high-momentum protons in neutron-rich nuclei.

"What this paper is saying is the reverse, that the protons actually have the higher-average momentum. And it's because they've all paired up with neutrons," Higinbotham says. "It's like a dance with too many girls (neutrons) and only a few boys (protons). Those boys are dancing their little hearts out, because there aren't very many of them. So the average proton momentum is going to be higher than the average neutron momentum, because it's mostly the neutrons that are sitting there, doing nothing, with nothing to pair up with, except themselves."

Higinbotham notes that the neutrons may also pair up briefly with other neutrons in short-range correlations and protons with other protons. However, these like-particle brief pairings occur once for roughly every 20 unlike-particle brief pairings.

Now, the researchers hope to extend these new findings to other, similar systems, such as the quarks in nucleons and atoms in cold gases. According to Or Hen, a graduate student at Tel Aviv University in Israel and the paper's lead author, he and his colleagues are already reaching out to other researchers.

"We expect that this will also happen in ultra-cold atomic gas systems. And we're having meetings with those researchers. If they find the same phenomenon, then we can use the flexibility of their experimental systems to go to extreme cases of very hard-to-study nuclear systems, such as the large imbalances of protons and neutrons that you can find in neutron stars," Or said.

To further that goal, Misak Sargsian, a lead coauthor and professor at Florida International University, said he's extending this work into his own theoretical calculations of neutron stars.

"Think of a neutron star like it's a huge nucleus, where you have ten times more neutrons than protons. The effect should be very, very profound for neutron stars. So this opens up a new direction for research," Sargsian said.

According to Lawrence Weinstein, a lead coauthor and eminent scholar and professor at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va., the scientists would also like to continue their studies of the pairs.

"We'd like to measure a lot more aspects of how protons and neutrons pair up in nuclei. So we know not just protons prefer neutrons, but how are the pairs behaving, in detail," he said.

This new result was made possible by an initiative funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy and led by Weinstein and Sargsian, as well as Mark Strikman, a distinguished professor at Penn State, and Sebastian Kuhn, a professor and eminent scholar at Old Dominion University. The data-mining initiative consisted of re-analyzing experimental data from completed experiments in an attempt to glean new information that previously had not been considered or was missed. A collaboration of more than 140 researchers from more than 40 institutions and nine countries contributed to the result. Researchers at two U.S. Department of Energy national labs, Jefferson Lab and Argonne National Lab, participated in the research.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science, the U.S. National Science Foundation, Israel Science Foundation, Chilean Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Technológica, French Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and Commissariat a l'Energie Atomique, French-American Cultural Exchange, Italian Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, National Research Foundation of Korea and the U.K.'s Science and Technology Facilities Council. CEBAF is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.Submitted by DOE’s Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility