- Number 294 |

- August 31, 2009

Biodevice project comes down to the nanowire

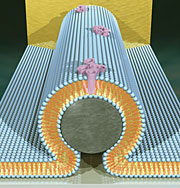

A nanobioelectronic device

incorporating an alamethicin

biological pore. In the core of the

device is a silicon nanowire (grey),

covered with a lipid bilayer (blue).

The bilayer incorporates bundles

of alamethicin molecules (purple)

that form pore channels in the

membrane.

Image by Scott Dougherty, LLNL

If manmade devices could be combined with biological machines, laptops and other electronic devices could get a boost in operating efficiency. Researchers at DOE's Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory have devised a versatile hybrid platform that uses lipid-coated nanowires to build prototype bionanoelectronic devices.

Mingling biological components in electronic circuits could enhance biosensing and diagnostic tools, advance neural prosthetics such as cochlear implants, and could even increase the efficiency of future computers.

While modern communication devices rely on electric fields and currents to carry the flow of information, biological systems are much more complex. They use an arsenal of membrane receptors, channels and pumps to control signal transduction that is unmatched by even the most powerful computers. For example, conversion of sound waves into nerve impulses is a very complicated process, yet the human ear has no trouble performing it.

“Electronic circuits that use these complex biological components could become much more efficient,” said Aleksandr Noy, the LLNL lead scientist on the project.

To create the bionanoelectronic platform, the LLNL team turned to lipid membranes, which are ubiquitous in biological cells. These membranes form a stable, self-healing and virtually impenetrable barrier to ions and small molecules. The researchers incorporated lipid bilayer membranes into silicon nanowire transistors by covering the nanowire with a continuous shell that forms a barrier between the nanowire surface and solution species.

“This ‘shielded wire’ configuration allows us to use membrane pores as the only pathway for the ions to reach the nanowire,” Noy said. “This is how we can use the nanowire device to monitor specific transport and also to control the membrane protein.”.

[Lynda Seaver, 925.423.3103.

seaver1@llnl.gov]