- Number 366 |

- July 2, 2012

Microscopy reveals workings behind promising inexpensive catalyst

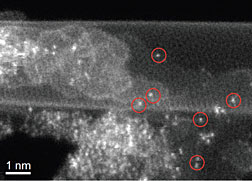

A carbon nanotube complex with promise

as a cheap catalyst was thought to have

nitrogen and iron impurities that lend the

material its desirable chemical properties.

Electron microscopy at ORNL confirmed that

the material's structure incorporates many

heavy atoms, such as the iron atoms circled

in red.

A newly developed carbon nanotube material could help lower the cost of fuel cells, catalytic converters and similar energy-related technologies by delivering a substitute for expensive platinum catalysts.

The precious metal platinum has long been prized for its ability to spur key chemical reactions in a process called catalysis, but at more than $1,000 an ounce, its high price is a limiting factor for applications like fuel cells, which rely on the metal.

In a search for an inexpensive alternative, a team including researchers from DOE's Oak Ridge National Laboratory turned to carbon, one of the most abundant elements. Led by Stanford University's Hongjie Dai, the team developed a multi-walled carbon nanotube complex that consists of cylindrical sheets of carbon.

Once the outer wall of the complex was partially "unzipped" with the addition of ammonia, the material was found to exhibit catalytic properties comparable to platinum. Although the researchers suspected that the complex's properties were due to added nitrogen and iron impurities, they couldn't verify the material's chemical behavior until ORNL microscopists imaged it on an atomic level. "With conventional transmission electron microscopy, it is hard to identify elements," said team member Juan-Carlos Idrobo of ORNL.

"Using a combination of imaging and spectroscopy in our scanning transmission electron microscope, the identification of the elements is straight-forward because the intensity of the nanoscale images tells you which element it is. The brighter the intensity, the heavier the element. Spectroscopy can then identify the specific element."

ORNL microscopic analysis confirmed that the nitrogen and iron elements were indeed incorporated into the carbon structure, causing the observed catalytic properties similar to those of platinum. The next step for the team is to understand the relationship between the nitrogen and iron to determine whether the elements work together or independently.

The team's findings are published in Nature Nanotechnology as "An oxygen reduction electrocatalyst based on carbon nanotube-graphene complexes."[Morgan McCorkle, 865.574.7308,

mccorkleml@ornl.gov]