- Number 443 |

- July 13, 2015

Discovering dwarf galaxies, one sticky at a time

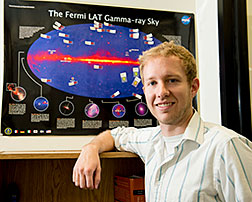

Alex Drlica-Wagner.

Photo: Reidar Hahn, Fermilab.

For Alex Drlica-Wagner, the most exciting day since joining DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory as a postdoctoral fellow occurred earlier this year: He and his collaborators on the Dark Energy Survey found new dwarf galaxy candidates, which could hold the key to understanding the invisible matter in our universe known as dark matter.

“Discovering things is the most exciting part of the job,” he says, “but it happens only once in a blue moon.”

Drlica-Wagner came to Fermilab in 2013, after doing research as a Stanford University graduate student at DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

“I had been working on searches for dark matter through gamma rays,” he says. “I saw an opportunity to use the Dark Energy Survey to search for new dwarf galaxies, which are one of the best targets for dark matter. Coming to Fermilab seemed like an amazing opportunity.”

The Dark Energy Survey is a 5-year project to map a large swath of the southern sky in unprecedented detail. The survey is carried out using a supersensitive, 570-megapixel digital camera mounted on the Blanco telescope in Chile.

“Going down to the DES site in Chile is really amazing,” says Drlica-Wagner, who also plays semiprofessional ultimate Frisbee for the Chicago Wildfire. ”Being there is a unique experience. You're on the top of a mountain, you're pretty isolated, and depending on what you're doing, sometimes you're working all night and sleeping all day. It's very different from your usual day.”

DES scientists expect to find more than 300 million galaxies, most so faint that their light is around 1 million times fainter than the dimmest star that can be seen with the naked eye. The DES camera, built at Fermilab, can record the light emitted by galaxies even if they are billions of light years away from Earth or are very small. Dwarf galaxies, for example, can have fewer than 100 stars and hence are remarkably faint and difficult to spot, even if they reside in the vicinity of our own galaxy, the Milky Way.

In his office, Drlica-Wagner keeps a map of the sky in gamma rays adorned with colored stickies. The objects tagged in red are previously discovered dwarf galaxies. The green stickies point out interesting gamma-ray sources.

“I tracked down a new color of sticky — yellow — for the new dwarf galaxies that we found,” he said.Submitted by DOE's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory