- Number 392 |

- July 8, 2013

Dahl aims to burst the dark-matter bubble

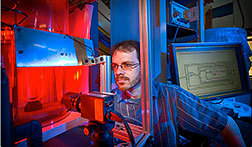

Eric Dahl (Credit: Fermilab).

Sometimes, when the day’s work is over, Eric Dahl sits in front of his computer and watches a live video of a clear vessel filled with a special liquid. He watches from a room on the sixth floor of Wilson Hall, the main building of DOE’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois; the vessel is 700 miles away, in a lab buried more than a mile underground in a mine in Ontario.

Most of the time, the liquid isn’t doing much. Some days, though, Dahl sees a bubble, and one day, one of those bubbles might revolutionize our understanding of the universe by providing direct evidence for a new type of matter particle. Dahl, an assistant professor at Northwestern University and a scientist at Fermilab, is one member of a small team working on the Chicago Observatory for Underground Particle Physics experiment, which is using bubble chambers to search for signs of dark-matter particles.

In a bubble chamber, a liquid is heated to beyond its boiling point, a state known as superheated. A particle collision with enough energy can create a bubble, and, using acoustics, scientists studying those bubbles can figure out what kind of particle interacted. The COUPP experiment, located deep underground at SNOLAB, uses in its quartz bubble chamber a fluid called iodotrifluoromethane, or CF3I. As a member of COUPP, Dahl analyzes the data from the bubble chamber and subjects smaller chambers to particle beams at Fermilab’s testing facility in order to calibrate the experiment. He is also contributing to the design of the next-generation chamber.

Dark matter, which accounts for 25 percent of all matter and energy in the universe, is frustratingly elusive: It has evaded explanation for 80 years, but may be essential to expanding the known world of physics.

“It’s really our strongest evidence that there is particle physics beyond the Standard Model,” Dahl says. “Once we do see dark-matter particles, that’s just the beginning of the story.”

For all its import and intrigue, dark matter itself didn’t immediately grab Dahl’s attention when he started studying physics. He wanted to be a string theorist. But after working on the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search to fulfill a graduate school requirement, Dahl realized he was an experimentalist.

From CDMS, he moved on to the XENON and LUX dark-matter projects, which are developing ever more powerful liquid-xenon dark-matter detectors. In 2009, looking for something new, he joined COUPP as a postdoc.

COUPP is small, but gaining ground. Dahl is one of about 15 people working on the collaboration. He recently recruited his first graduate student and hopes to bring more on board.

“We’re at the stage where it would be appropriate to start building an army to tackle all of these things,” Dahl says. “Build the army and then we take over the world, right? That’s our goal. It’s to take over the dark-matter world.” — Laura DattaroSubmitted by DOE's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory